The transformation of Medellin, from violence to innovation

Journal Post #13: March 6th 2023, Park City Utah

Hola and welcome to Where on Planet Earth! In case you got here by accident and are not yet a subscriber, sign up below! For more visuals on our travels follow us on IG @whereonplanetearth

We are HOME! We didn’t want to spend a full year without snowboarding, so we are taking a little break from the travel go-go-go. We will only be here a month, but I am already loving it. Honestly, we were sort of ready for a reset - a parenthesis - a few weeks of nothing on the agenda except to snowboard, cook, read, and write (plus go to doctors, unpack and repack for the next phase, see friends, create content, plan upcoming trips, etc, so not all chill). We have never lived in any of our homes without having a job, so this is a *real* treat. I mean, we can go snowboard on a Tuesday morning! Total and absolute luxury. And I get to cook in my kitchen… and words can’t explain how much pleasure this gives me.

Anyways, I will share more about this reset time in an upcoming post - how does it feel to be home, both good and bad - but for now let me tell you about Medellin’s transformation! From being the most dangerous city in the world, to a world-class smart city. From having a population without access to basic services, to having one of the highest rates of education and health care access in South America. A city ruled by crime transformed into a digital nomad heaven.

How could a transformation this intense happen? How did they do it?

In summary: sustained investment in social innovation and urban development

Medellin is a pretty new city, founded around 350 years ago. Since its beginnings Medellin was built on segregation. The indigenous community there, the colonizers over here. Later on, African slaves there, rural migrants over here. Throughout its history many sectors of society have been absent from its social projects, and this fueled conflicts and urban violence.

Diversity was not seek nor promoted, the power was held by white people and their goal was to exclude black and indigenous communities from any discord.

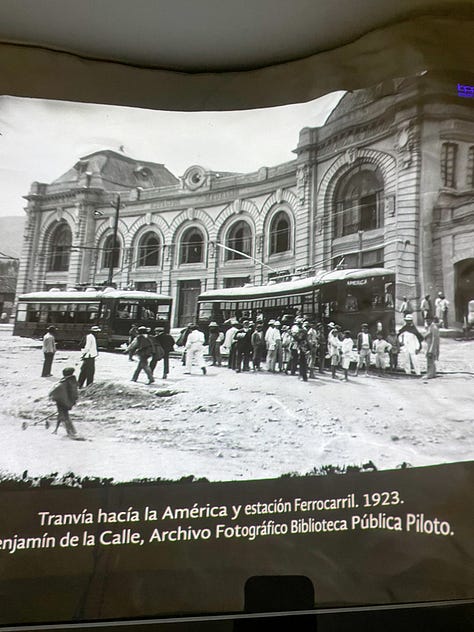

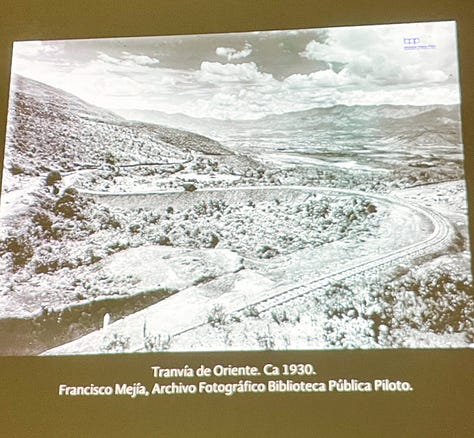

Once trains arrived, the city was transformed - now it was connected. This made it easy to get stuff in and out, and even to the sea. Commerce - mainly textiles - and mining became central to Medellin’s economy. Segregation continued however, with the high class living in some neighborhoods and the poor - indigenous, black, rural migrants, mixed raced, farmers, artisans - living in other places.

Between 1948 and 1958 many migrants reached the city escaping from violence in other parts of the state and the country. This period, called “The Violence”, started after the assassination of left-leaning populist presidential candidate Jorge Gaitan. During this ten-year civil war, in which more than 200,000 people were killed, Medellin grows exponentially and all the newcomers settle in the peripheries of the city.

To end the conflict, the Liberal and Conservative parties agreed to establish a bipartisan political system known as the “National Front”, in which these two parties rotate power every four years, restricting the participation of any other political party in the electoral process.

Before moving on to the 1960s I think it’s important to clarify who are the three main players - criminal groups - in Medellin’s urban conflict:

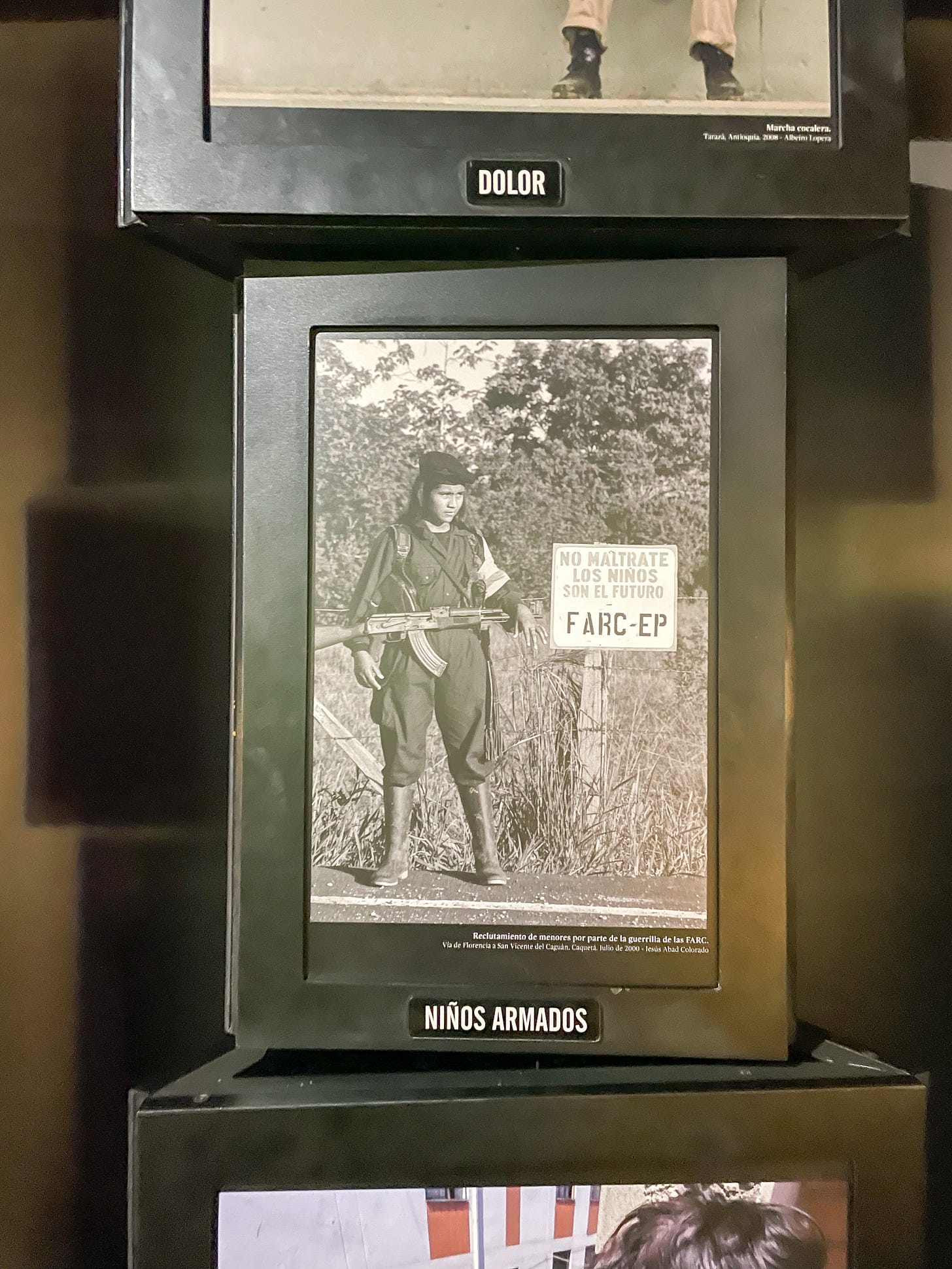

Guerrillas: communist groups initially formed as self-defense groups seeking social justice, which rapidly deteriorated into criminal groups. The FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forced of Colombia) is the most known one, but there were many others (M-19, ELN, EPL).

Paramilitaries: right-wing groups created by the Colombian military, and US-backed (from the start) to fight the guerrillas. These also became criminal groups, controlling a large majority of the drug trade and causing most civilian deaths during the conflict.

Drug Cartels: organizations focused on the international trafficking of cocaine. The Medellin Cartel was the most powerful with Pablo Escobar at the helm - and this is likely what you think about when you hear about Colombia and Medellin.

All these groups interacted with each other in one way or the other, with the cartels and paramilitaries working extremely closely. The military is also part of the mix, and in many cases should be labeled as just another criminal group. Also, all groups were involved in the drug trade, either by controlling land used to cultivate coca leaves (and taxing for it) or directly managing a piece of the trade to fund their operations.

Ok, let’s continue.

In 1966 the FARC is established as a reaction to the “National Front” and also as a reaction to attacks towards communist groups by the Colombian military and US-backed paramilitary groups (a common and repeatedly used tactic of the C.I.A. in many Latin American countries).

The FARC starts as a peasant self-defense communist movement focused on social justice. But, very rapidly, they start funding their operations with taxation of the illegal drug trade, ransom kidnappings, robberies, extortion, etc.

With time, other guerrilla groups appear, more paramilitary groups are created, and the cartels became increasingly powerful. They all terrorized civilians in many ways, by fighting each other in the middle of crowded cities, by kidnapping people, by extorting businesses, etc. This goes on for decades.

Medellin became the most violent city in the world in the early 1990s and keeps that disgraced title throughout that decade

The city is dubbed “Murder Capital of the World”

In 1991, 16 people are murdered every day on average

When we visited Comuna 13 - what used to be the most dangerous neighborhood in the city - we learned how unstable and scary life could be during that time. Our tour guide told us her family arrived in 1980 and invaded what was then just an empty mountain - many arrived running from violence and others just wanting to own a little piece of land. There was no government presence, not water or electricity. Then, in 1990 the FARC came to the comuna, “they were a group of farmers against the government with good ideas, initially”, our guide told us, “they were doing social work, and even gave mothers flowers on Mother’s Day.”

Once the community accepted them they started doing what they called a “social cleansing”. Supposedly getting rid of criminals, but in reality they would kill anyone they saw as a potentially threat. It wasn’t uncommon to wake up to dead people on the street. The community, including children, just grew up around the violence.

“It was common for us kids to look out the window and see dead people on the streets”, our guide shared, “They killed my 17 year old brother just because he had friends in another comuna… The guerrilla thought he was with the paramilitaries, so he was shot point blank".

Many military operations were done to get the guerrilla out of the neighborhood - innocent people were always killed in the cross-fire - but it wasn’t until 2002 that this mission is accomplished with Operation Orion, what is believed to have been a joint operation between government military and paramilitary groups. So, the guerrilla is gone, but guess who takes their place? Paramilitaries, of course.

In contrast to the guerrilla visibly violent methods, the paramilitaries waged a silent war in the neighborhood. There were no more people shot in the streets, but hundreds started disappearing. Years later, they found a giant mass grave under a garbage dump. Even to this day the government hasn’t taken out and identified most remains.

Eventually, the paramilitaries demobilize and leave the neighborhood in 2004. But, this time gangs take their place. Still, the neighborhood starts living in relative peace in comparison to previous decades.

And then comes the real key in the transformation: investment

The government decides to finally invest and support Comuna 13, and many other undeserved areas in the city, with social projects. In 2008 a cable car is built to integrate the comuna with other neighborhoods. This was the first time a gondola was constructed exclusively for public transportation in the world. Then, in 2011, electric escalators are built, which are a game changer! These escalators allow people to climb a very steep hill in only 6 minutes instead of what used to be a 25min hike up. This not only transforms the locals quality of life, but it also attracts tourism. People are curious about these outdoor escalators and the ton of gorgeous street art in the comuna. The community understands the value of tourism and organizes to support it. You can now visit the neighborhood - one of the safest in the city - and take tours with locals (like the excellent one we did), use the cool escalators, see superb art performances, eat yummy street food, and admire the incredible street art (all done by local artists!).

This is just one example of how Medellin was transformed, but the pattern is similar throughout many other examples. Several City Mayors, starting in 2000, took listening to their constituency seriously. They revamped the city’s education system, implemented initiatives to guide youth away from gangs, upgraded health care systems, added millions of square feet of public spaces and renovated parks, built new museums and sports facilities, added electric buses and a city-wide free bike-sharing service plus 60 miles of bike lanes!

Then, a high-tech digital perspective started to be introduced with the implementation of security systems on accident-prone highways, the installation of hundreds of free public Wi-Fi zones as well as internet-education centers, the introduction of “innovation districts” to provide office space and seed funding to high-tech start ups - which has resulted in hundreds of companies from many countries setting up operations in the city and generating thousands of jobs - the implementation of sensors to monitor rain and soil movements on hillsides throughout the city to monitor risks of flooding and mudslides, and the list goes on and on. This impressive development has become a model for urban planning around the world.

Medellin, with its incredibly violent and tragic history, today booms with tourists and has one of the highest rates of education and health care access in South America!

None of this makes Medellin a perfect city. There is still crime, and gangs, and drug trade, but the city’s homicide rate is one-twentieth of what it was in 1993, and nearly two-thirds of those who lived in poverty have emerged from it. We can say, with certainty, that there is a lot to learn from their story.